Fah Thai features – WORLD OF STONE.

By Denis Gray

It doesn’t take long to fall under the spell of Banteay Chhmar, one of the greatest monuments of the Angkorian Empire but still little known to the outside world following centuries of abandonment and, more recently, revolution and war. While Angkor Wat, Bayon and other temples near Siem Reap now receive an average of 7,000 visitors each day, this Buddhist monastery complex a three-hour drive from that tourist boom town daily welcomes just two.

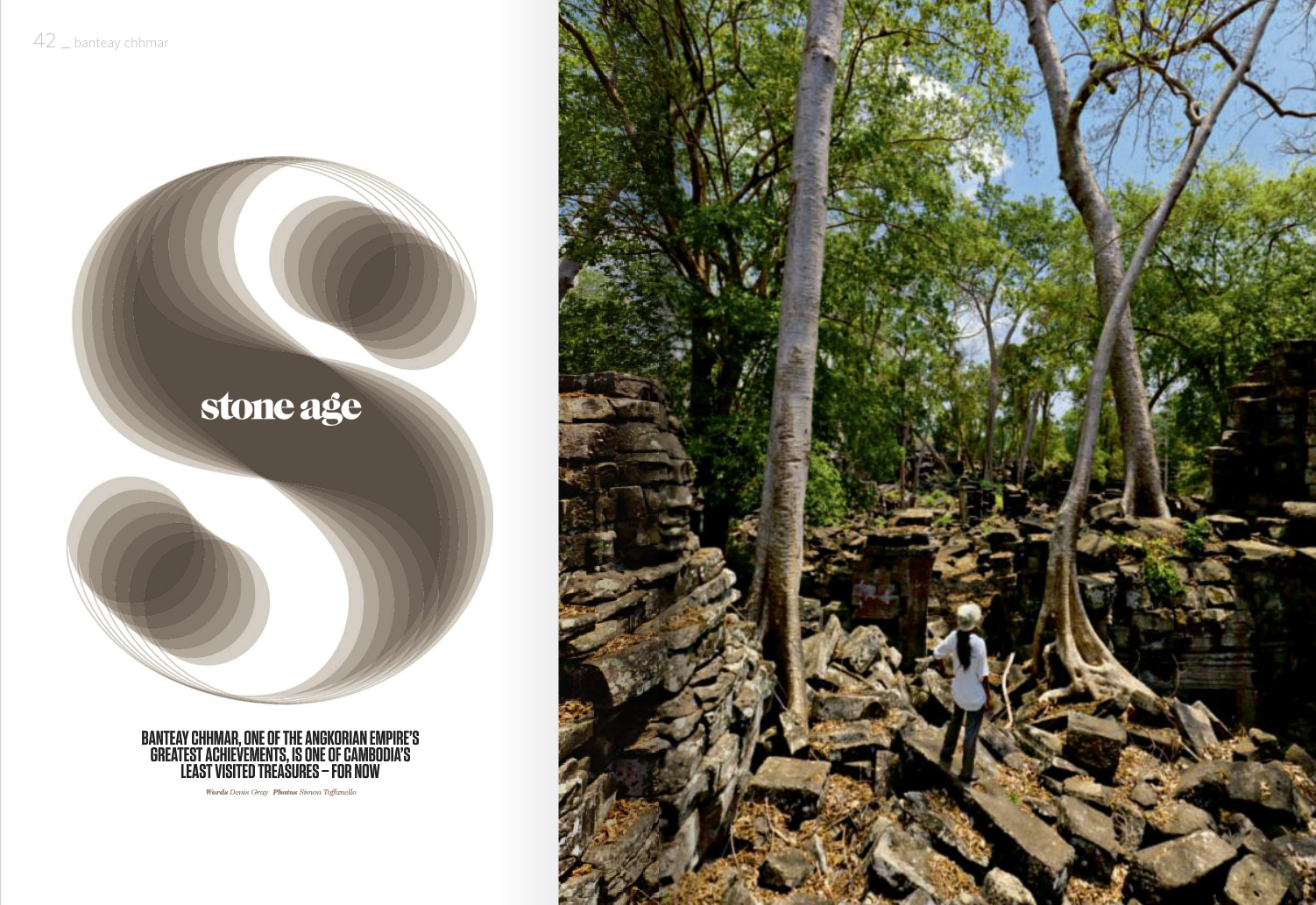

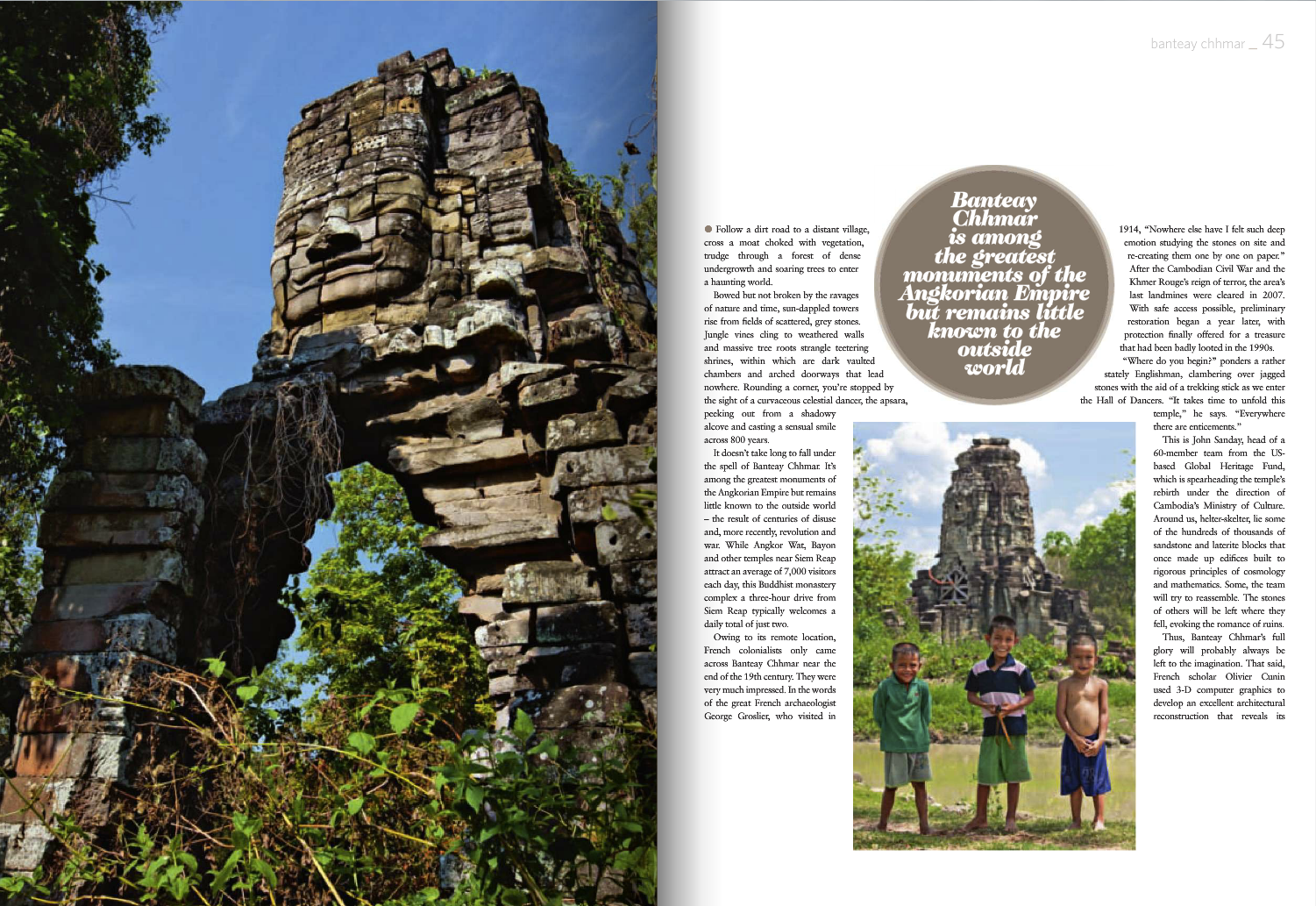

Towers that have withstood the siege of nature and time rise from fields of scattered grey stones dappled by sunlight shimmering through the green canopy. Jungle vines climb up weathered walls. Massive tree roots strangle teetering shrines. There are dark vaulted chambers still intact and arched doorways that lead to nowhere. Then, around some corner, from a shadowy niche, a curvaceous celestial dancer, the apsara, stops you with a sensual smile cast across 800 years.

It doesn’t take long to fall under the spell of Banteay Chhmar, one of the greatest monuments of the Angkorian Empire but still little known to the outside world following centuries of abandonment and, more recently, revolution and war. While Angkor Wat, Bayon and other temples near Siem Reap now receive an average of 7,000 visitors each day, this Buddhist monastery complex a three-hour drive from that tourist boom town daily welcomes just two.

Given its remote location, the French colonials only came across Banteay Chhmar near the end of the 19th century – and they were more than impressed. When the great French archaeologist George Groslier visited in 1914, he enthused that “nowhere else have I felt such deep emotion studying the stones on site and re-creating them one by one on paper.” Following the Khmer Rouge reign of terror and an ensuing civil war, the area’s last landmines were only cleared in 2007. With safe access possible, preliminary restoration began a year later with protection finally offered to a defenseless treasure that had been badly looted in the 1990s.

“Where do you begin?” ponders a rather stately Englishman, clambering over jagged, slippery stones with the aid of a trekking stick as we enter the Hall of Dancers. “It takes time to unfold this temple,” he says. “Everywhere there are enticements.”

This is John Sanday, head of a 60-member team from the US-based Global Heritage Fund which is spearheading the temple’s rebirth under the direction of Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture. Around us, helter-skelter, lie some of the hundreds of thousands of sandstone and laterite blocs that once made up edifices constructed to rigorous principles of cosmology and mathematics. Some, the team will try to put together again. The stones of others will be left where they fell, evoking for some the romance of ruins.

Thus Banteay Chhmar’s full glory will probably always be left to the imagination although an excellent architectural reconstruction using 3-D computer graphics has been developed by French scholar Olivier Cunin, revealing its stunning scale. The main temple measures 750 by 700 meters and is enclosed by a 60-meter-wide moat. All this is encased in an archaeological area of about 12 square kilometers which also includes nine satellite temples and a large baray or water reservoir.

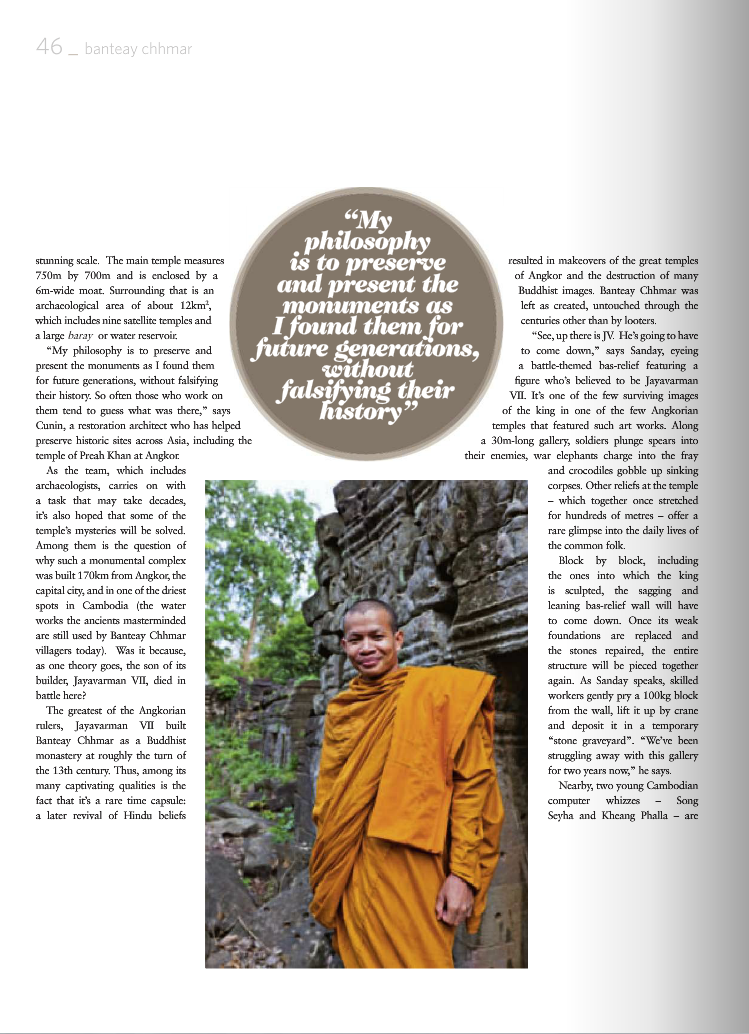

“My philosophy is to preserve and present the monuments as I found them for future generations without falsifying their history. So often those who work on them tend to guess what was there,” says the restoration architect who has helped preserve historic sites across Asia, including the 12th century temple of Preah Khan at Angkor.

As the team, which includes archaeologists, proceeds with a task that may take decades, it is also hoped that some of the temple’s mysteries will be solved, among them why such a monumental effort was made 170 kilometers from Angkor, the capital city, and in one of the driest spots in Cambodia (the water works the ancients masterminded are still used by Banteay Chhmar villagers today). Was it because, one theory goes, the son of its builder, Jayavarman VII, died in battle here?

This greatest of the Angkorian rulers built Banteay Chhmar at the end of the 12th century or beginning of the 13th as a purely Buddhist monastery, and thus among its other wonders it has remained a rare time capsule because a later revival of Hindu beliefs resulted in make-overs of the great temples of Angkor and the destruction of many Buddhist images. Banteay Chhmar was left as created, untouched through the centuries except for the looting.

“See, up there is JV. He’s going to have to come down,” says Sanday looking up at the figure of a man generally believed to be Jayavarman VII on a bas-relief vividly depicting a bloody battle. It is one of the few surviving images of the king in one of the few Angkorian temples that featured bas-reliefs. Along a 30-meter-long gallery, soldiers plunge spears into their enemies, war elephants charge into the fray and crocodiles gobble up sinking corpses. Other reliefs at the temple – which together once stretched for hundreds of meters – offer a rare glimpse into the daily lives of the common folk.

Bloc by bloc, including the ones into which the king is sculpted, the sagging and leaning bas-relief wall will have to come down, its weak foundations replaced, the stones repaired, and then the entire structure pieced together again. As Sanday explains, skilled workers gently pry a 100-kilogram bloc from the wall, lift it up by crane and deposit it in a temporary ‘stone graveyard.’ “We’ve been struggling away with this gallery for nearly two years now,” he says.

Nearby, two young Cambodian computer whizzes - Song Seyha and Kheang Phalla – are pioneering a shortcut to the reassembly process through three-dimensional imaging. This work-in-progress is one of the temple’s towers recently damaged in a severe storm. Some of its 700 stone blocs have been removed or collected from where they fell and each one will be placed on a turntable and videographed from every angle. Since like a human fingerprint, no stone is exactly alike, still to be finalized software should be able to fit all the blocs into their original alignments after they are repaired. “We hope that with one push of the button all the stones will jump into place to solve what we are calling `John’s puzzle,’” says Sanday.

As Sanday climbs around the tower’s scaffolding, workers below drill holes through two sandstone blocs of a lintel that will be bound together with steel rods. He can’t say enough about the skill and dedication of his Khmer staff, many of them barely literate rice and cassava farmers recruited from the village in keeping with the Global Heritage Fund’s philosophy of bettering the lives of those living around historic sites.

“You have to have the community buy into a project by gaining some revenue from it,” Sanday says. “We can’t protect it. They have to be the protectors.”

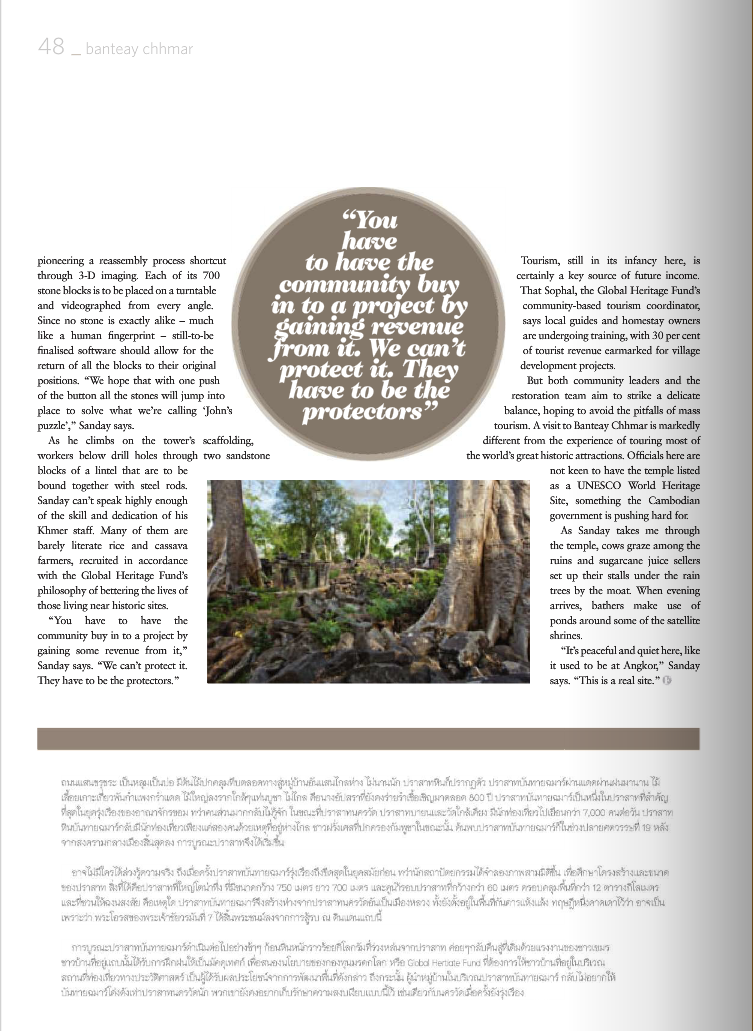

Tourism, still in its infant stage here, is certainly a key source of future income. That Sophal, the Fund’s Community-Based Tourism Coordinator, says local guides and homestay owners are being trained, with 30 percent of tourist revenue going into village development projects.

But both community leaders and the restoration team aim to strike a delicate balance, hoping to avoid the downsides of mass tourism because experiencing Banteay Chhmar today is very different from that at most of the world’s great historic attractions with guides shepherding tourists along prescribed pathways flanked by souvenir shops and eateries. They are not keen to have the temple listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, something the Cambodian government is pushing hard.

As Sanday takes me through the temple, cows graze among the ruins, sugar cane juice sellers set up their stalls under the rain trees by the moat, and when evening comes bathers dip into ponds around some of the satellite shrines.

“It’s peaceful and quiet here, like it used to be at Angkor,” Sanday says. “This is a real site.”

By Denis Gray